How Does Your Garden Grow? On Letting Plants Lead: In Conversation with Charlie Harpur, Head Gardener at Knepp

On a hot July day last year, with the grasses at full sway and the air thick with insects, pollen and hum, we went to Knepp to see head gardener Charlie Harpur. The day had the kind of heat that slows your steps and sharpens your senses. As the bees droned, heavy with work, there was the feeling of everything being particularly alive, bugs everywhere, the whole place just breathing summer. The journey down the long driveway, passing free-roaming, long-horn cattle in the re-wilded parkland and farmland, sets the scene to arrive at the walled garden. To get into it, you must step through the magical large oak gate, like a portal from a previous world of castle croquet lawn and swimming pool, into a glimpse of the future of gardens.

The entrance to The Walled Garden

Wild Carrot (Daucus carota) and Echinacea pallida

Knepp is close to us, geographically, it sits by Shipley, just 20 minutes west from us. I knew it before the re-wilding shift, when it was still a more formal, castle-adjacent garden. English in the traditional sense, filled with cottage favourites, clipped edges, careful intention. The walls of the walled garden. The magnolia. The smoke bush. The cypress cutting a dark, vertical lines skyward. Those bones still remain, but now they are softened, loosened in grip, given permission to be held by something wilder and fully, unimaginably different.

Firstly there’s the walled garden, filled in with crushed building material waste and the planting guided by experts like Tom Stuart-Smith and James Hitchmough, where over 800 species were planted to establish resilient plant communities. Gravel paths now bloom with herbs, and a former croquet lawn has been transformed into diverse hummocks that encourage native plants to seed. And then there’s the old potager garden, whose paths still echo their way through, but plants now ramble across them, no longer held entirely in check. The grand greenhouse in the potager garden still stands, and it’s where the garden is still productive with vegetables and there are sweet peas grown for the house. (For our fellow sweet pea enthusiasts - Charlie favours Matucana for its scent and history.) The hierarchy here has truly shifted; the plants are the protagonists, they lead, they decide, and the result of all this feels spectacularly painterly. Splatters of colour in combinations so subtle and so alive that no human hand could ever convincingly recreate them. There is a swell to the place, a hum, and an atmosphere that I respond to far more deeply than what came before. I think it is truly beautiful.

Charlie cutting Matucana Sweet Pea in the old potager garden

The Walled Garden

Charlie Harpur and I regularly walk together with our families and sighthounds, and those days are some of my great joys. He is a dear friend and, without question, one of my favourite gardeners. I have learned so much from him over the years, not least the art of paying attention. As we walk, Latin names tumble out of him, unannounced and unselfconscious, punctuating the landscape like small sparks of delight. But what he really practises and teaches is not nomenclature. It is relationship. Between soil and root, insect and flower, human and place.

Paris and I went to visit Charlie at Knepp the summer before last. It wasn’t our first visit there, and it certainly hasn’t been our last. Each time we return to Knepp, the garden has has shifted again. Never static. Never finished. Always in conversation with the season, the weather, the wider ecology that now shapes it. It’s been so interesting to witness, and to no longer see gardening as control or ornament, but as collaboration, and Knepp feels so special for that.

This following conversation grew out of our friendship and those walks with Charlie and his family. Out of a shared fascination with what happens when humans step back just enough to let life step forward. And out of a question that has sat at the heart of my own gardening, and of my new book, How Does Your Garden Grow: how do we take these big ideas that Knepp owners Charlie Burrel, Isabella Tree, and Charlie Harpur have been practising about re-wilding, abundance, ecological thinking, and translate them into our own gardens at home? Into borders, pots, walls, and paths we live alongside every day.

What follows is a distillation of that thinking. A conversation with Paris, Charlie and I about letting plants lead, about trusting processes that feel uncomfortable at first, and about finding ways to invite a little of Knepp’s generosity, softness and wild intelligence into the spaces we tend ourselves.

We have edited the spoken transcript with the lightest of touches, to clarify any overlaps in conversations.

Milli: For people who might have only heard the word rewilding in passing, how would you describe it in a garden setting like this? It feels like such a big idea to translate to a domestic space.

Charlie: It is a big idea, but at its heart it is quite simple. Rewilding means restoring natural processes. At Knepp we have seen that, once you let those processes run, complexity starts to build: mosaics of habitats appear through interactions among animals, plants, and the environment. In a garden, the animals are mostly us: the gardener is the keystone species, so we are the ones guiding the process. It is really about restoring natural interactions and allowing a shifting mosaic to form. That is achievable even at garden scale.

Paris: When you call the gardener a “keystone species,” what do you mean by that? It is such a great phrase.

Charlie: This is a human-made ecosystem. Each gardener’s choices, our tastes and habits, differ slightly, and that actually increases complexity. Like different herbivores browsing different plants, gardeners curate by choosing. Our interventions shape everything else.

Milli: You often talk about the garden as a “mosaic,” or sometimes a “kaleidoscope.” Why both words?

Charlie: A mosaic suggests pattern; a kaleidoscope adds movement. A functioning ecosystem is never static. Many formal gardens aim to freeze time, with cloud-pruned box, crisp topiary, and borders kept perfectly “just so.” Nature does not work like that. As the keystone species, our job is to allow succession and then steer it gently when needed.

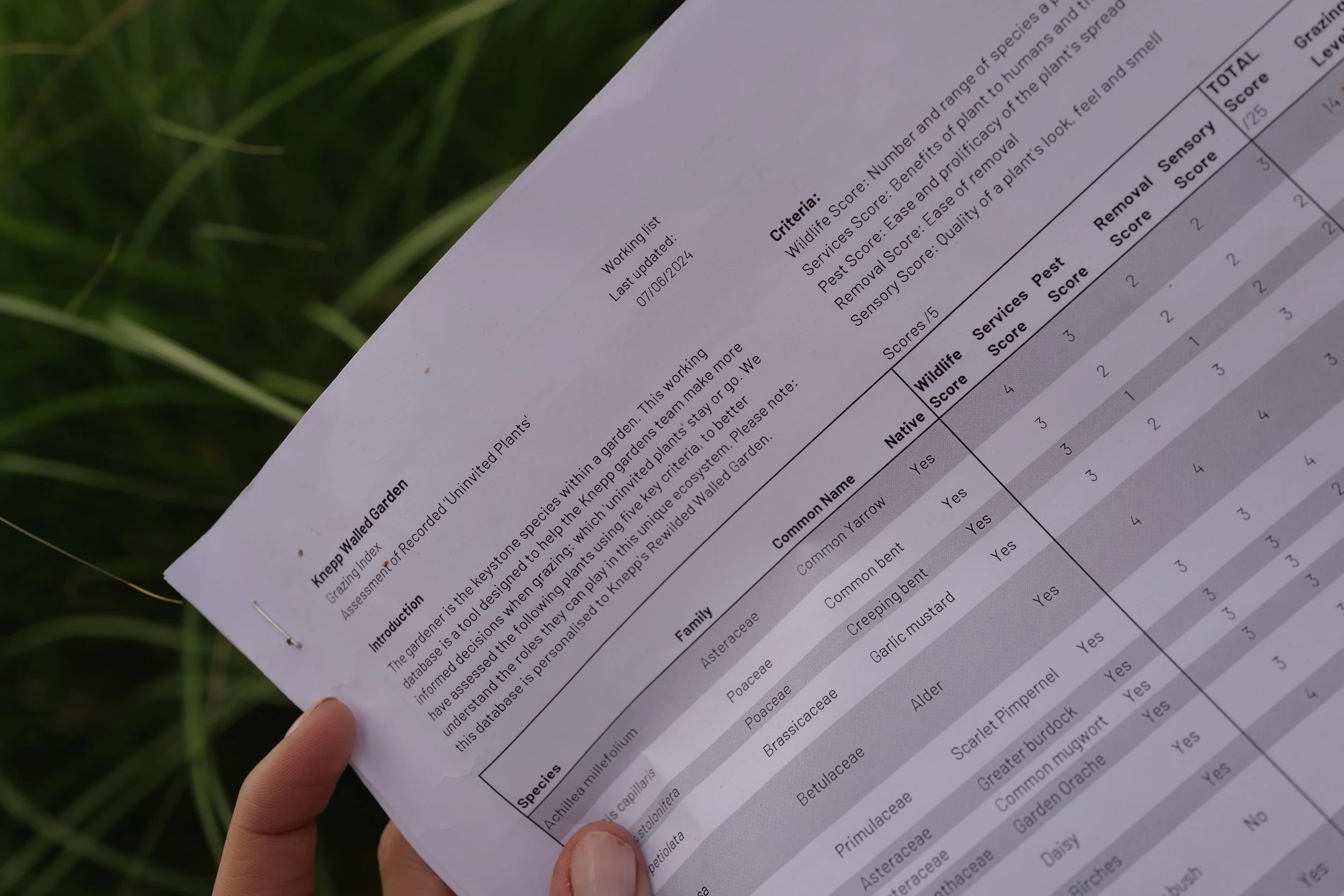

Paris: So it is less about control and more about observation. You have been using something called a “grazing index,” right? What is that exactly?

Charlie: It is a practical tool we have made up for ourselves. We list every plant that appears without being planted, self-seeders, wind-blown arrivals, hitchhikers in soil. There are 110+ of those species here now. Most are native and valuable to wildlife. The index helps us decide how to treat each one.

The Grazing Index

Milli: People are often taught to pull up anything they did not plant, all the so-called weeds. Why do you keep them?

Charlie: Because weeds are not always the villains. They can be crucial. In our first summer, when it hit 40°C, some “weedy” plants behaved as nurse plants, shading young seedlings. Once they had done that job, we removed them, but they had already helped others survive. Value depends on context.

Paris: That is a lovely way to think about it, plants working in succession. But how much do you actually edit the garden? It feels like a garden still. It doesn’t feel wild here, in the sense of abandoned.

Charlie: Quite a lot of editing goes on. We spend time thinning and balancing dominant self-seeders like wild carrot. The key is balance, humans acting as grazers. With something like buddleia (Buddleja), a superb nectar source, we keep it browsed into shape rather than eliminating it.

Milli: I love that idea of the gardener as a grazing animal. Can you give an example of a plant that people might usually pull up, but you now see differently?

Charlie: Definitely ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris). It is often hated, but around 30 insect species depend on it entirely, and 200+ are supported by it somehow. If you remove ragwort, you lose those specialists, like the cinnabar moth. We manage it by grazing before it seeds, not by eradicating it.

Ragwort Jacobaea vulgaris and Verbena bonariensis

Paris: Let’s talk about how this all started. What was the original design brief, and how much has the garden changed since then?

Charlie: The brief was intentionally open-ended: maximise biodiversity. We varied the topography and soil types to create as many microhabitats as possible. Two and a half years ago, this was a croquet lawn. Now, no square metre is like the next. We planted about 800 species initially; including all the uninvited arrivals, we are now around 1,100.

Milli: That is incredible. And because this is part of a bigger experiment, you have been monitoring it scientifically too?

Charlie: Yes. We did soil baselines and an invertebrate survey, repeating the same transects and sampling methods. After three years, we saw a +33% jump in recorded insect species, from about 333 to 434. For a young, compact site, that is really encouraging.

Paris: Your soil approach is so interesting; it is almost the opposite of what most gardeners do. Can you talk about that?

Charlie: We reused construction waste and poor substrates deliberately: roughly 75% crushed farm building with 25% sandy subsoil in places. Rich soil can give you fewer, bigger plants. Poorer, varied substrates often give more species. In the veg beds we do build fertility with our own compost, but in the wilder areas we embrace the tough soils for diversity.

Milli: So even “bad” soil becomes a kind of design tool. How do you handle cutback and structure through the seasons, especially for wildlife?

Charlie: Nothing in nature happens uniformly, so we do not do a big February clear-out. We nibble, cutting selectively at different heights and times. We keep hollow stems for overwintering, seedheads for food, and standing material for cover. It is all about creating options.

Paris: For people reading this who might want to try a bit of rewilding at home, where would you start?

Charlie: Think diversity leading to complexity. Do not hold the garden to one tidy standard. Mix it up: vary when and how you cut back, let some volunteers stay and curate them, use different substrates, keep some patches damp and others dry, and watch what appears. Let plants show you what niches they fill, like docks loosening compacted clay with their deep roots.

Monarda (left) and Charlie holding buddleia (Buddleja), (right)

Milli: And when you are scoring plants in that grazing index, what are you actually judging them on?

Charlie: Five things:

Wildlife value, how many insect species they support

Invasiveness or management cost, how much effort they need

Ecosystem service, whether they help the soil or other plants

Human use, whether they are edible, medicinal, or useful

Aesthetic or sensory, whether they look or smell good

One fun example: a bird dropped a rose seedling that grew in the wrong place. Instead of pulling it out, we trained it into an informal rose dome. A bit of chance turned into design.

Paris: That is such a good image. What does your year look like as gardeners here; is it very different from a more conventional rhythm?

Charlie: Very different. Rewilding is not neglect. We run tours and workshops, over 130 so far; we plan seed lists and cropping for the kitchen garden; and we manage multiple areas across the estate with a small team of three. Horticulturally, spring starts the selective grazing, and the rest of the year is about steering the balance and observing change.

Milli: The colours in here feel so harmonious, all those purples and yellows. But you have had flooding and extreme heat. How does it all hold together?

Charlie: The lowest area floods for months; it is heavy clay. Heat bounces off the walls and we hit ~40°C that first summer. Some big-leaved plants failed, but others like alders, rushes, and sedges arrived by themselves. We basically run two planting logics: Mediterranean species on the free-draining rubble that finish before the heat, and prairie species, asters, rudbeckias, silphiums, echinacea, in wetter zones for late-season colour. There is a lull between the two peaks, and that is fine. It is seasonal rhythm.

Paris: Are there particular plants that you are especially fond of at the moment?

Charlie: Yes, quite a few!

Wild quinine (Parthenium integrifolium) for its persistent white heads.

Spanish broom (Spartium junceum) which has just finished after months of bloom.

Moon carrot (Seseli gummiferum), luminous seedheads and architectural shape.

Milkweed (Asclepias sp.), a fantastic wildlife plant.

And a white Galtonia candicans thread that shifts flowering time every year.

But honestly, the most exciting thing is not a single plant; it is the life the garden now supports. The answer to “why are we doing this?” should always be because it is good for biodiversity.

Milli: That is a beautiful place to end. But before we wrap up, any small details visitors might miss, things that quietly make the place work?

Charlie: We are adding a pergola of oak posts for shade and to grow vines. Rainwater harvesting feeds gravity-fed drip lines in the veg garden. We avoid synthetic netting where possible. And we are experimenting with planting pockets in the gravel paths: little mosaics for drought-lovers like sea kale, thymes, and lavenders. They are tiny gestures, but together they all build resilience.

Earlier this month we caught up with Charlie again to ask a few more questions in order to tug on some of his ideas a little more-

On Control and Wildness.

Knepp has become a model for what happens when we let go of control. As a gardener, where do you still feel the urge to intervene, and where have you learned to stand back and trust the process?

Charlie: Letting go of control is more straightforward in large, well-connected landscapes where the ecosystem can function fully. There is constant change which creates dynamic opportunities for different forms of life: grazing herbivores roam, dig, trample and fertilise, kept on their toes by the threat of predators; trees fall and decay, letting in vital light. At a garden scale, within walls and fences, the gardener is the proxy disturbance agent. In the gardens at Knepp we learn from these examples of natural processes – and more - to create similar complexity in the garden to increase opportunity for life. We observe the garden ecosystem, trust the processes unfolding and only really intervening to give them a steer, rather than impose a fixed picture. Examples might be addressing an imbalance, such as a plant that is smothering everything else, or pruning (grazing) to let in light and air. Ants making hills, or pioneering plants which spring up are appreciated for the wildlife opportunity, services or beauty they can provide. (Those deemed truly problematic are then grazed out!) There is also a degree of intervention reserved for more aesthetic purposes: We call this the ‘cue to care’ – a term coined by US academic Joan Iverson Nassauer in her paper ‘Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames’. Perceived neglect is what we humans can’t stand. Mowing a path through long grass is a good example of this ‘orderly frame’ around a ‘messy ecosystem’ which shows the viewer that someone is caring for the garden. This perception helps us all relax, and see the opportunity within. So, in the gardens at Knepp, where visitors can see, we keep paths clear, create ordered bundles of our cuttings rather than leave them all strewn about in chaos. We are artistic in our work to show these important ‘cues to care’ which helps the visitor to engage and enjoy the garden.

On Beauty and Perception.

Rewilded spaces can challenge our traditional sense of beauty. What does beauty look like to you now, after years of working in a landscape that is constantly rewriting the rules?

Charlie: Complexity and opportunity are beautiful. Rather than in midsummer when the garden is full of colour, I would put the frosty December version of the gardens at Knepp forward for the beauty award. Seedheads provide food, dead stems and rusty grasses provide shelter. Varied heights of plants, different shapes and textures keep the eye moving and mind interested. Add a layer of icy hoar frost on top of this and you have incredible visual sensory beauty, as well as the knowledge that, even at a very harsh time of year, the garden is a valuable refuge for a spectrum of life.

On Gardening for the Future.

When you think about tending land today, do you imagine you’re gardening for someone, for the next generation, for wildlife, or (we can go even more existential on it, and garden for time itself)?

Wow, what a question. I like the idea that by gardening for wildlife, and by locking in carbon in healthy living soils, you are gardening for the next generation. We are at a very critical time for nature, and gardens and gardeners are important parts of the solution to slowing and even reversing decline. We should garden with the belief that we can save it all. But it has to be said that we need to use and enjoy our gardens, and what gives me a lot of satisfaction is the simple action of growing vegetables and flowers with and for my daughter. But that’s another way of gardening for the next generation!

On Practice and Philosophy.

Your work sits at the meeting point of horticulture and ecology. How do you balance the gardener’s instinct to curate with the ecologist’s impulse to observe?

Charlie: I had visions of spending a lot of time crawling through the garden with a hand lens studying insects rather than gardening before I started at Knepp! We definitely do look at the life we find whilst we’re gardening, but it’s a big place and there’s always a lot to get done! A good way of setting aside that healthy observation time is to set a moth trap to monitor nightf lying moths in the garden. These beautiful moths can be identified and enjoyed before we start work! Monitoring wildlife is really important as it helps inform our intervention as gardeners.

On Change and Continuity.

The Knepp landscape is constantly evolving. no two seasons are ever the same. How has that constant change shaped your own sense of patience, progress, and what it means to “finish” something?

Charlie: Each season has been starkly different. Extreme heat, drought, wet, cold, and wind. Each extreme is sudden and really tests the plants - and us gardeners. Plants may die as a result, but with death comes two things: opportunity for other species, and data to help you select something more suitable for your garden. At first, I saw these lost plants as failures, but death is a vital part of a healthy ecosystem, despite not being something we like to talk about as gardeners. And it’s not just death! Plants also naturally have boom and bust years: some need a wet spring to germinate and thrive, whilst others get a headstart on the season without. Waiting to see what happens, and rolling with the conditions is exciting. Predictable abundance just wouldn’t be as rewarding (unless of course you are eating the plants or cutting them for flowers, when it makes total sense..!) I think it’s important to see a garden as a process rather than a finished outcome. Functioning ecosystems are always on the move.

On Translation and Influence.

You’ve been advising us as we shape our new studio garden, a much smaller canvas than Knepp, but one inspired by its principles. How do you think ideas from large-scale rewilding can translate meaningfully into domestic gardens, or even window boxes? And what might we lose, or gain, in the translation?

Charlie: The first thing I would say is that connectivity is key. We nearly always consider gardens in isolation – as islands. But when you think about how your window box or back garden connects to next door’s, for example, or to the trees on the street, or the park down the road, then it helps you to make decisions as to what you do with your piece of the wider garden habitat mosaic! Diversity is key, after all, so why not have later flowering plants in your window box if next doors are all over by the mid-season? Or leave your grass long if next doors lawn is mown weekly? If you have a larger space, you can widen the spectrum of habitat conditions further: have areas of longer and shorter grass; have wetter areas and drier areas; as well as diversifying vegetation types too, from ground layer, to shrub layer, to tree layer, and so on! In the UK in particular, our landscapes tend to be frequently cut up by roads and fences, so trying to exactly emulate a larger rewilding project just isn’t realistic. We must therefore think outside of the box: be the proxy herbivore or disturbance agent (see question 1!) and see your garden as part of the bigger picture. The larger the landscape, the less human intervention is needed to mimic natural processes which would naturally play out in a functioning ecosystem.

Quick-fire

Charlie, let us know what plants you’d choose if someone wanted to bring a little of Knepp’s spirit into their own garden, whether a large plot or a window box, what are the first plants you’d tell them to grow?

Charlies go-to’s for:

• structure: grasses such as Panicum virgatum cultivars or Stipa pseudoichu. Even tall wild biennials such as teasel (Dipsacus fullonum) or mulleins such as Verbascum thapsus will give excellent structure.

Evergreen shrubs such as Helichrysum orientale do a lot of work for us.

• pollinators: Ivy! (Hedera helix) or an umbel such as wild carrot (Daucus carota) or moon carrot

(Seseli gummiferum)

• resilience: Dianthus carthusianorum, which is useful on a range of scales, and ladies bedstraw

(Galium verum) handles drought and alkaline soils well.

• long season of interest: For larger spaces, trees such as Wild Service (Sorbus torminalis)

which is a hard-working tree and more climate-resilient than rowan, or crab apples such as the cut-leaf crab (Malus transitoria). Good flowers, good fruit, good autumn colour.

• sheer joy: Campanula patula or Delphinium grandiflorum – both seed sown, tiny, and

captivatingly blue!

Thanks so much for your time and wisdom Charlie!

You can book your visit to the Knepp gardens and re-wilding project here: https://knepp.co.uk/garden-visits/